Nobody can reliably predict how markets will perform in the next six, 12, or 24 months. However, we have a very good sense of how markets grow and function over longer periods of time, and this long-term perspective is central to our work developing portfolios on behalf of our clients. As advisors, our objective is to build portfolios that allow our clients to capture the market’s long-term trajectory while managing short-term risk.

This is all well and good in theory, but in practice, investors have to contend with two emotions that can make it very difficult to stick to this strategy: fear and greed.

- From an investing standpoint, fear can refer to one of two things. The first is the fear of losing money, which we saw in March of last year when the market experienced a significant downturn. When the market rebounded, we saw the other side of fear: fear of missing out. With equity markets at record highs and several sectors seeing unusually strong returns, this fear of missing out is the largest “fear” in the marketplace today.

- The second emotion, greed, is most common when the markets have seen an exceptionally strong run and investor confidence is high. As we know, recency bias can be challenging to overcome, and the desire to “chase return” is a common theme in the current market environment as well.

Both of these emotions were explored in detail by Maury Fertig in his 2006 book, The 7 Deadly Sins of Investing. And while both emotions are entirely normal, they can negatively impact investor performance when they encourage “market timing” — or the belief that an advantage can be gained (or losses avoided) by tactically entering or exiting the market.

What the data tells us about market timing

There is an old saying in wealth management that successful investing is not about timing the market, but about time in the market. This concept is supported by research, and data has continually shown that investors who try to time the market routinely underperform investors who stick to a defined asset allocation strategy.

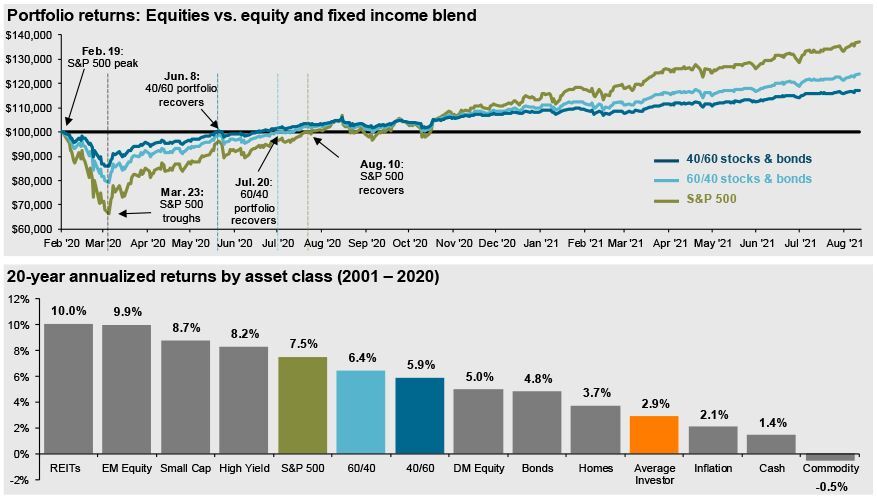

Between 2001 and 2020, a portfolio of 60% stocks and 40% bonds saw an average annual return of 6.4%. Over this same time period, the average investor saw just a 2.9% annual return. Emotional factors, which encouraged investors to attempt timing the market, were key factors driving the spread in performance. The chart below shows this data, along with the performance of several other sectors over the 20-year period.[1]

This analysis highlights how you can still do well with a balanced approach to investing — your main objective is to avoid the return profile of the “average investor.” In our experience, staying committed to a defined asset allocation strategy is the best way to achieve that objective, even if it means giving up some of the S&P 500’s return in exchange for greater risk management.

Standing on the sidelines: another form of market timing

Market timing doesn’t just occur when buying or selling assets — it can also happen when deciding whether to participate in the market at all. Choosing to stay out of the market (or significantly de-risk) is itself a form of market timing.

Today, with the market at record valuations, there can be a desire to sit on the sidelines and wait for prices and valuations to return to more “reasonable” levels. However, this isn’t a risk-free decision.

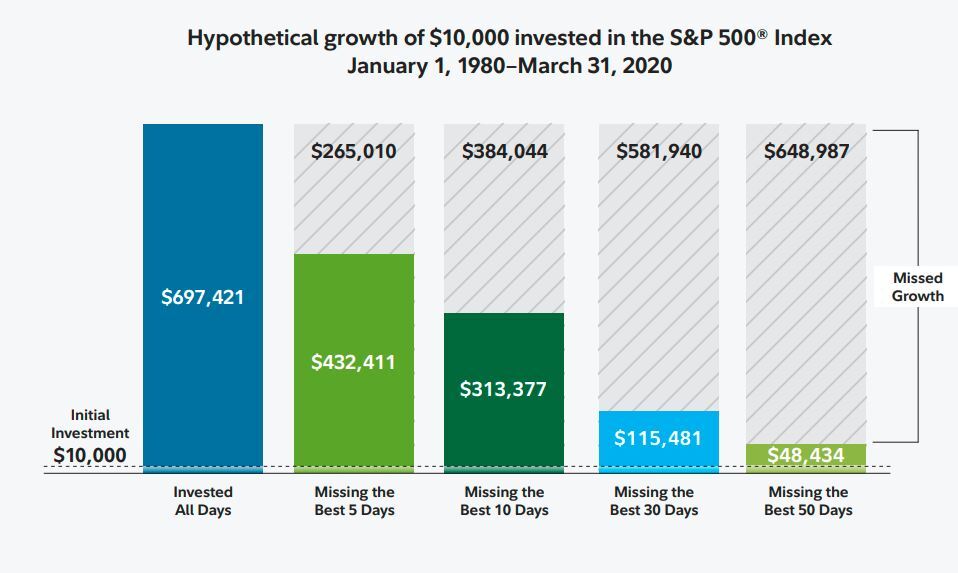

The chart below shows the hypothetical growth of $10,000 invested in an investment that tracked the S&P 500 index from 1980 to 2020.[2] Missing out on just five of the best-performing days during that period resulted in a staggering 38% reduction in performance. And for investors who missed the 30 best days over this 40-year period, we see an 83% reduction in performance.[3]

In other words, a significant proportion of your long-term performance in the market will likely come from just a handful of big days, and nobody can reliably predict when those big days will occur.

Seek opportunities within the context of your defined strategy

Although the research shows us that market timing is unlikely to be successful, you can still be opportunistic within the context of your asset allocation strategy. Portfolio rebalancing is a great opportunity to look for assets that hold relative value when compared to their peers, allowing us to be opportunistic within the marketplace but not emotional.

For example, consider the 60% stock and 40% bond portfolio we referenced earlier: after a year of market movement, this portfolio might be 65% stocks and 35% bonds. To rebalance this portfolio, we would need to sell 5% of the equity portion and buy this dollar amount in the bond portion. In order to do that, we will need to define which stocks to sell and which bonds to purchase. This process creates an opportunity to sell strength (overperformers) and to buy weakness (underperformers) in a way that targets value opportunities.

This strategy is the exact opposite of market timing: it’s buying and selling done in alignment with your asset allocation strategy, not in response to the ebbs and flows of the market. If this approach and mindset sound like the right fit for your investment objectives, we invite you to connect with our team.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: DAVID MCGRANAHAN

A Partner at Relative Value Partners, David McGranahan serves as Financial Advisor, assisting with business development and client experience management.

With more than 25 years of experience in the financial services industry, David came to RVP from Credit Suisse, where he worked in New York, London and Chicago. He most recently served as Managing Director and Head of Wealth Management for the Midwest Region. Prior to overseeing Credit Suisse’s Midwest Private Banking operations, David worked his way through the ranks, filling many roles including Head of Fixed Income and Hedge Fund Initiatives for CS HOLT, Head of U.S. Equity Sales (Europe), Institutional Equity Sales and Fixed Income Research Analyst, when he first started at the firm in 1991.

David earned his Bachelor of Arts from Princeton University, where he majored in Politics with a certificate in Political Economy and Latin American Studies. He went on to complete a Masters of Management with a concentration in Finance and Strategy from Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management.

Disclosure

Information contained in this article is obtained from a variety of sources which are believed though not guaranteed to be accurate. Past performance does not indicate future performance. This article does not represent a specific investment recommendation.No client or prospective client should assume that the above information serves as the receipt of, or a substitute for, personalized individual advice from Relative Value Partners, LLC which can only be provided through a formal advisory relationship. Clients of the firm who have specific questions should contact their Relative Value Partners counselor. All other inquiries, including a potential advisory relationship with Relative Value Partners, can be directed here.

[1] J.P. Morgan Asset Management, Diversification and the average investor (here)

[2] The hypothetical example assumes an investment that tracks the returns of a S&P 500® Index and includes dividend reinvestment but does not reflect the impact of taxes, which would lower these figures. “Best days” were determined by ranking the one-day total returns for the S&P Index within this time period and ranking them from highest to lowest.

[3] Fidelity, Stay invested: Don’t risk missing the markets’ best days (here)

Relative Value Partners merged with Kovitz Investment Group Partners, LLC as of August 2024. All Insights are opinions of the author as of the posting date. Any graphs, data, or information in this publication are considered reliably sourced, but no representation is made that it is accurate or complete, and should not be relied upon as such. This information is subject to change without notice at any time, based on market and other conditions. Past performance is not indicative of future results, which may vary.